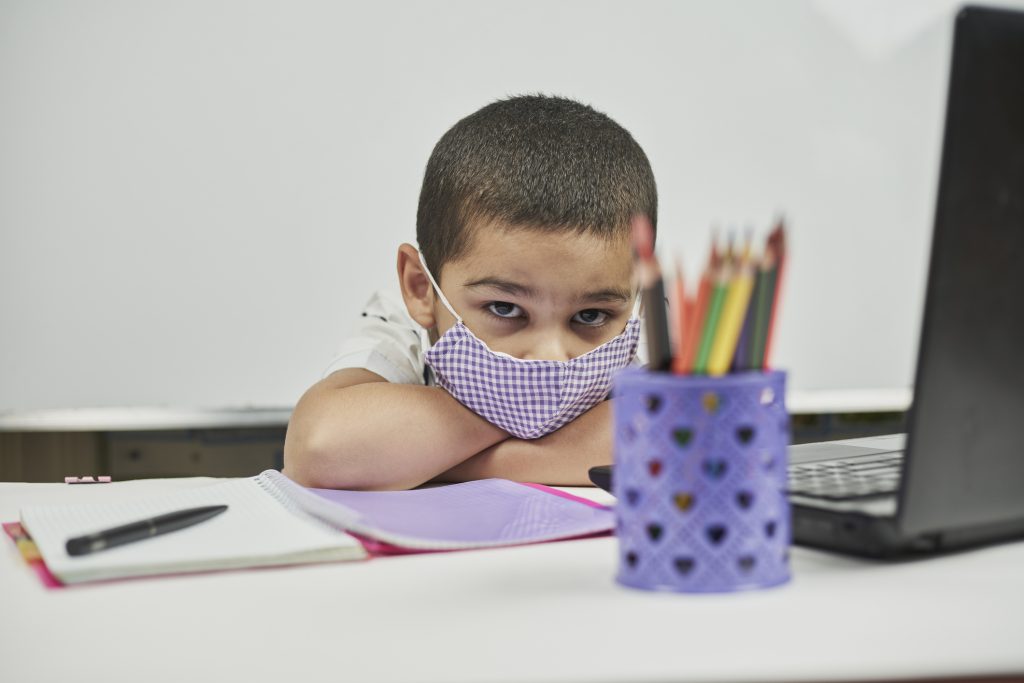

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, English learners (ELs), like many students, already faced challenges at school. How to engage and teach ELs when they’re learning from home is another new challenge educators are facing. Beginning with factors that affect all students, here are some ideas to help.

Maslow Before Bloom

In a time of widespread job losses and economic uncertainty, we must put Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs before Bloom’s Taxonomy when it comes to thinking about the social and emotional needs of our youth. If students don’t have their basic needs met, we can’t expect them to show up and perform to academically high standards or to do well on standardized tests. More than ever, we want to make sure kids are emotionally healthy. The experience of having school buildings closed, of being removed from their routine and their teachers and their friends, has been traumatic for many children. In addition, many parents work in industries that provide essential services, which means these parents are still expected to work during the pandemic, leaving their children home alone. Consider the benefit of providing families with resources—such as books or websites—that support social-emotional learning as a means of lessening the anxiety faced by both parent and child during these challenging times. Now let’s turn to the issue of distance learning itself. According to Benjamin Herold, “the messy transition to distance learning in America’s K–12 education system as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic has been marked by glaring disparities among schools. Among the most significant are gaps between the country’s poorest and wealthiest schools around access to basic technology and live remote instruction, as well as the percentages of students who teachers report are not logging in or making contact” [The Disparities in Remote Learning Under Coronavirus (in Charts), Education Week, April 10, 2020]. Distance learning requires access both to high-speed internet and adequate devices at home. It should be no surprise that both are less available in lower socio-economic communities, affecting synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities. However, access to remote learning opportunities depends on technology not only within the home but within the district as well. Rural schools, for example, often suffer from not only poor connectivity but limited staff and technical expertise. Even in the best of situations, where technology is accessible both at home and at school, providing resources to families is important for two reasons: 1) for general communication, and 2) to help families whose children have not previously experienced distance learning.

Support the Parents, Support the Child

Whatever the language proficiency in the home, supporting ELs during COVID-19 means finding a way to communicate with parents or guardians in a language they understand. This can often be best accomplished by anchoring to what is already familiar to them: community organizations, migrant centers, acculturating centers, centers with adult ESOL classes, etc. There are two benefits to this approach: 1) centers and organizations such as these are used to working with speakers of many languages, and 2) adults are used to working with these centers and organizations. In both instances, not only have relationships been developed but also adults know how to engage in the process of obtaining information and/or support. Supporting an English learner academically brings us back to the challenge every EL faces: learning a new language, learning about a new language, and learning through a new language. This means finding a way to support their learning of English and in English. In such a situation, the importance of synchronous learning becomes clear. Students learning a language need interaction with others speaking the language.

Reassessing Expectations

We must also continue to set goals while reassessing expectations. For example, for young EL students, the specific benchmarks preschoolers must meet to move into kindergarten involve socializing with their peers, which is not happening right now. Three months is a long time for a preschooler to be away from their group setting. Those three months are a large percentage of their life, and if they are not developing those social skills now, those benchmarks for kindergarten can set them back. Older students face different challenges. High schoolers may have time limits to meet specific expectations to graduate. They may still be working on learning English or may have been doing intensive work in class knowing they could graduate on time. Now they’re going to be behind six months or a whole year, and they might not be able to catch up and finish. What does that mean for policy and expectations dealing with students who are graduating? And what does it mean for their future?

Funding and the Future

A lot of funding to support ELs comes from the federal and state government.1 Funding is based on meeting expectations for third, sixth, and eighth grades, but those assessments haven’t happened this year. Schools will have to think about the formulas they’re going to use to receive the money they need to continue supporting the learning of every child. ELs are already trying to learn English. No matter what program they’re in, they have extra stressors put upon them as they go through school. Adding the pandemic-related strains on top of a more challenging educational path is going to be stressful. All students deserve an education filled with academic rigor, as well as understanding and compassion—especially now.

Carol Johnson is a bilingual educator and national education officer at Renaissance. She holds a PhD in second-language acquisition and teaching, specializing in how people learn second languages.

Doris Chavez-Linville, MSEd, is the director of English learner innovations at Renaissance. A former migrant education teacher, she is an advocate of equity in education through making technology resources of high rigor and high quality for all learners.

Renaissance has resources to support parents in multiple languages available at https://www.renaissance.com/renaissance-at-home/.

Links

1. https://www.renaissance.com/resources/funding/