Pandemic teaching was hard. It stretched and pulled us. We worried about our students and their well-being. But we did it. We supported students’ learning to the best of our ability and worked hard to ensure that students knew we cared about them. Throughout the experience of remote, distance, hybrid, hyflex, and simultaneous teaching, we did learn a lot. Unfortunately, the narrative does not focus on the unexpected learning that we all experienced. Yes, there is unfinished learning that needs to be addressed, but so many of us (and our students) learned things that we did not expect to learn. When we ask about this, we tend to hear about three main topics: technology, social and emotional learning, and self-care. But we also learned a lot about what works to engage students in learning.

In this article, we will focus on what we learned about accelerating learning. The research evidence pre-dates the pandemic, but we have found it useful to revisit this information as we strive to address unfinished learning. Importantly, we are not focused on remediation, which is deficit-oriented thinking that focuses on gaps and loss and might result in lowered expectations. The surface logic of remediation might be: they didn’t learn what they needed to in 2020–21, so they can’t learn what they need to this year. There’s a long-term danger in this line of thinking, because we’re not just talking about the 2021–22 school year. This faulty logic could be perpetuated for every year that this cohort of students is in school.

Instead, we focus on acceleration. We acknowledge that there is unfinished learning and that we teachers have the power to impact students’ learning. We’ll focus on aspects of acceleration that we can all use to ensure students learn more and better.

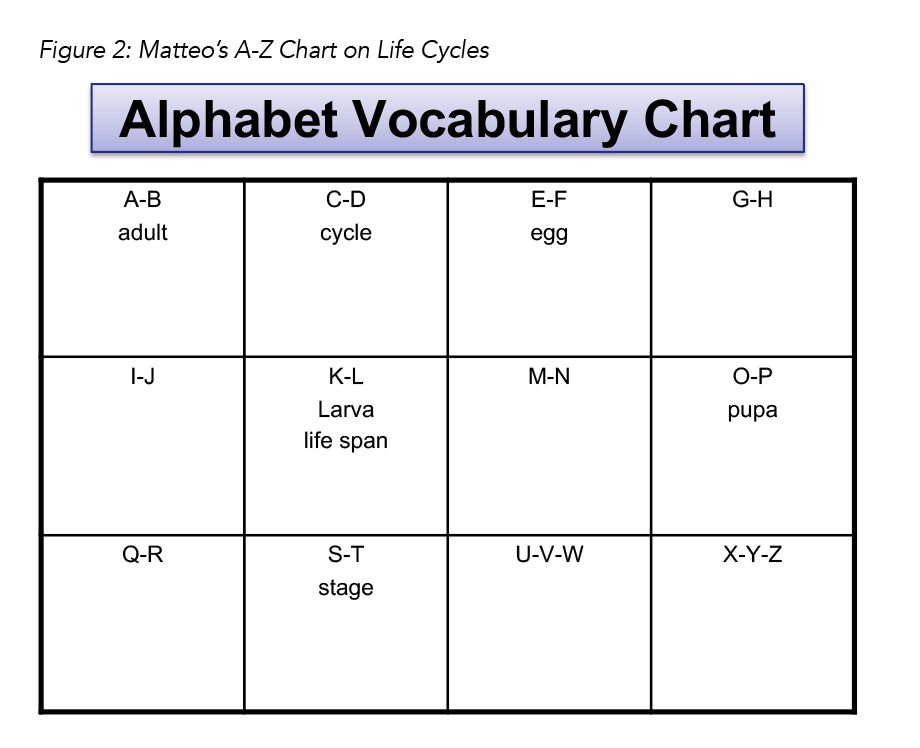

Identify skills and concepts that have yet to be learned. We need to assess students to figure out what they already know and what they still need to learn. There is evidence (e.g., Nuthall, 2007) that, on average, 40% of instructional minutes are spent on content students have already mastered. We do not have time to spend on skills and concepts that students already know. But it’s not as simple as cutting out 40% of the stuff we normally teach. Different students know different things, and we need quick tools to identify what they know and what they still need to learn. For example, we could use an A–Z chart for students to identify all the terms they know about a topic before teaching it. Matteo’s list of words about life cycles can be found in Figure 2. These are all the terms he knew before the lessons started. Now imagine if all the students in the class had egg and larva on their charts. We don’t need to teach that. And what if 33% of the students had pupa on their charts? It’s time to design small-group lessons. When considering what students already know and what they need to know, remember that not all the content is critical. As our colleague John Almarode likes to say, “There are things that students need to know and things that would be neat to know.” With your team, identify the nonnegotiable, essential, critical content and focus more time on that. After all, a lot of the content standards cycle and recycle, while deepening.

Build key aspects of knowledge in advance of instruction. Learning theorists suggest that we go from the known to the new. Background knowledge is important and mediates who learns what. We all learned how to make interactive videos during pandemic teaching, and we can continue to collect or produce these resources for students. When students need background knowledge or vocabulary, we can create videos and load them into our learning management system for students to access. Systems like PlayPosit and EdPuzzle allow students to interact with the content and provide teachers with data about students’ interaction with the videos. Let’s harness the technology learning educators and students have gained and use it during face-to-face instruction. Wide reading also helps build background knowledge and vocabulary, and we need to get more reading materials into students’ hands and support them to read outside of the school day. When we ensure that students develop key aspects of knowledge in advance of instruction, the lessons can move faster and students will acquire deeper understandings.

Increase the relevance of students’ learning. For some students, school is boring. When students do not see relevance in their learning, they are much less likely to self-regulate. And self-regulation is important, as we all want students to focus, set goals for their learning, manage their time, remain on task, and ask for feedback. One key to ensuring that students engage in self-regulation is to guarantee that they see relevance in the learning. We use three clarity questions with students:

What am I learning today?

Why am I learning this?

How will I know that I have learned it?

The first question requires that teachers clearly explain what students will be learning that day. These learning intentions serve to focus the class on the topic at hand but do not necessarily need to be announced at the outset of the lesson. But at some point during the lesson, students should know what they are learning. The second question allows the teacher to discuss the relevance and importance of the learning. Relevance may involve using the learning outside of the class or it may be for something interesting in class. Or it may be an opportunity to learn about yourself and how your brain works. For example, a geometry teacher teaching about midsegments of triangles noted that volcanologists used this information to determine the size of volcanos and later in the lesson noted that props for a play could be measured using this information, and she gave an example. The third question requires that teachers be clear about what success looks like. What does it mean to have learned something? A video of teachers talking about learning intentions and success criteria can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqBdPjSE–g.

Create active, fast-paced learning experiences. The pace of the lesson is important. In remediation, the temptation is to slow down. That’s the opposite of the acceleration research, which suggests that the lesson needs to be fast-paced and active. This concerns some educators, as they worry that students will be left behind. We are not suggesting rushing through lessons trying to “cover” all of the curriculum, but rather that the pace keep students engaged and moving in their learning. Of course, it’s also important to maintain wait time. There are points in the lesson at which students are provided time to listen, process, perhaps translate, and build the courage to respond. And there are times when the teacher is ensuring that the pace is engaging. Watch a first-grade teacher’s pace with half of the students learning remotely and half in the classroom. Notice the pace and the value of learning intentions and success criteria.

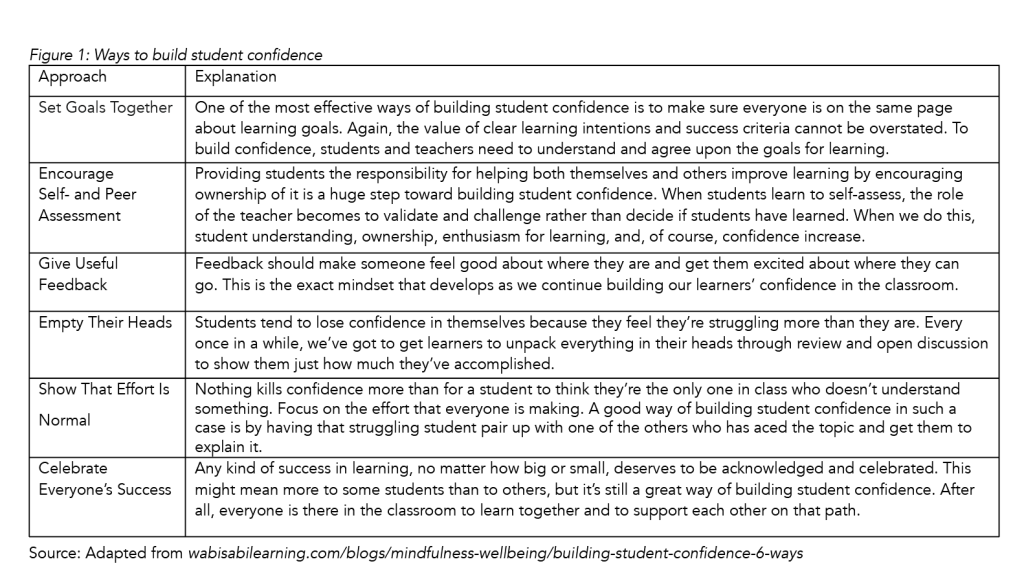

Rebuild student confidence. Some students have a damaged relationship with learning. Not all of them. Many students still love learning and are confident in their progress. And some students did quite well over the past couple of years. But some students are not confident and they do not understand the impact of their efforts on their success. When students do not have a strong sense of agency, they begin to exert less effort. Figure 1 contains a list of ways to build student confidence. In addition, watch as teacher Sarah Ortega meets with one of her students to build agency. Importantly, Ms. Ortega noticed that her student did not realize that what she did impacted her own growth in reading. Ms. Ortega provides details about the actions her student took and attributes the success to those actions.

Our students are where they are. And it’s our turn to accelerate their learning. There is good evidence that we can use to address the unfinished learning that some of our students have as we contribute to the rebound of our learners. As a final note, take pride in the impact you have on students’ learning and social–emotional development. You are making a difference, and students are benefiting as a result of your efforts.

References

Nuthall, G. (2007). The Hidden Lives of Learners. NZCER Press.

Nancy Frey and Doug Fisher are professors of educational leadership at San Diego State University and teacher leaders at Health Sciences High. They are the co-authors of Rebound and How Tutoring Works.