“I know all these students well. I don’t know their data.” Anonymous

Do you remember taking exams in school? Do you remember the feelings of anticipation, validation, triumph, or sheer horror while looking at your own grades? Those weekly spelling tests on Fridays caused me a lot of unnecessary angst. We’ve been looking at data our entire lives! Especially as educators. Language classrooms are not exempt from conversations centered around student performance, expected outcomes, standards, grades, pass/fail, and the like. Data, a four-letter word, and how it is used (or not) has resonated with me lately. Especially after preparing two school leaders for a data meeting. The quote above is seared in my memory. How is it that we spend so much time doing the work that we miss some of the most important opportunities to do the work better? We need data, not simply for its numbers, percentages, averages, or grades, but as a tool for equitable instruction.

In a recent blog post, Leslie Villegas1 (2023), at New America, provided a pulse check on Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) goals2 for English learners. Are states on track with what they proposed in 2015? My work is centered around and aligned with supporting educators of linguistically diverse learners, K-12 students who are eligible for language support services, in succeeding the goals they set for students. Simple questions with complex answers are what I pose to my partners. Some of those questions include;

- What are the intended outcomes?

- What data is collected?

- What is the data telling us or not?

- Is what is being done working for students?

- How is English language proficiency / performance data being utilized?

- How is the data positioned?

- Are students a part of data analysis and related discussions? If not, how come?

Responses vary but most often the answers or attempts to answer lead to requesting more professional learning. Yes, I’m in agreement with more data centered professional learning opportunities for language educators but only if we make the data comprehensible, usable, timely, and empowering. We need to make the data CUTE.

C – Comprehensible: Do we understand what data is being presented and why? Is the data too convoluted and congested? More data is not always part of the answer but rather more of certain types of data such as qualitative data and less common data.

U – Useable: Is the data something we can use to make different / better choices? Does the data provide more context? Do we have data points for all four domains of language? Do we have data that is aligned to and in support of the Language Instruction Educational Programs (LIPM)? How can we include but move beyond demographic data?

T – Timely: How can we collect, analyze, disseminate, and use data more efficiently? The time we dedicate to collecting data is oftentimes nowhere near equal to the amount of time we spend analyzing it.

E – Empowering: Are we using asset-based lenses when it comes to understanding, using, and sharing data? If so, who is being empowered? Is it all gloom and doom or more butterflies and cupcakes? Are students part of and at the center of data based discussions?

Have you asked similar questions to these? I’m interested in hearing more about those conversations and the actions that may follow. In regard to ESSA goals, Villegas states, “how some of these goals were framed reflect a lack of transparency and accessibility in helping the public understand ELs’ progress.” If the data is not CUTE, then it is difficult to use it to make improvements and celebrate student success. Data is not supposed to be another barrier, we have plenty of those. We need the data to be in service of the work educators and students are doing to foster critical thinking, develop autonomous learners and to uphold linguistic justice.

In a recent conversation I asked if students were included as part of reclassification practices. Reclassification, as it is referred to in some learning communities, is when students have reached proficiency in the target language and may no longer be eligible for language support services. This is also known as an “exit criteria” which are most often controlled by states and districts. Someone asked me what that might look like, having students part of these

exit criteria discussions. This counter question affirmed the need to include students. Through surveys, questionnaires, focus groups, and exit interviews we could ask students about their own sense of efficacy as multilingual humans. What goals and aspirations do these students have? How have we, as their educators/advocates, supported them? What does this look and sound like beyond an assessment score? See April’s (2023)3 edition of Pass the Mic for more about what students want from their learning communities.

A few months ago, I was fortunate enough to present at Harvard’s Strategic Data Project4 Convening with two colleagues. The conference theme, Battle Lines, is described on the website as,

The public conversation about education is as contentious as ever. What role do data play in our battles, past and present? What are the measurement implications? How do we fight for high standards of data- and evidence-use, and ultimately for the students we serve?

The three-day event was filled with courageous conversations and included educators from early learning to adult education settings. Our session; Bridging the Divide for Multilingual Learners, It’s a Civil Rights Issue, addressed myths and misconceptions around how English language development and English language proficiency data points are incorporated (or not) into leadership coaching practices. Rachelle, who supported a partner in the early stages of building capacity to better support linguistically diverse learners, affirmed the importance of being intentional with a plan and not operating with a spirit of assumptions. Her advice to district and school leaders is also framed around the CUTE model;

Comprehensible – Most data points are on the surface and most conversations about marginalized students land there as well. This is why we are not making the gains to increase literacy and math scores for all students.

Usable – Go deeper with unpacking what the data is showing. Ask the right cognitive questions, such as who is our LIPM working for and who is it not?

Timely – Think about what supporting a leadership team across 8-10 months looks like. In the first weeks the data discovery process to determine if the goals set are adequate and/or need to be adjusted. This helps school leaders move away from assumptions and supports them in getting to the root cause of the inequity.

Empowering- hold space for supporting critical conversations about students not being served and instruction that is not effective. When you effectively identify how to improve instructional practices for your most marginalized, all students benefit from better instruction.

As part of the Science of Reading panel, moderated by Emily Hanford, Panelist Tyra Harrison a Data Fellow Supervisor, explained the importance of using data more strategically by asserting;

“The Strategic Data Project is an important lever for change and innovation in education. The energy and sheer brain power generated at the gathering is an ongoing opportunity to share levers for engaging stakeholders5 at every level around authentic data usage. The biggest lever isn’t the data; its access and “know how”. The conversations answered the ever present “and what?” that tends to linger when stakeholders are presented with data that doesn’t have connection and context. Helping our data experts begin with the end AND end users in mind is the goal. We know literacy is a civil rights issue – we have the capacity and insight to create a new story. It starts with conversations like these.”

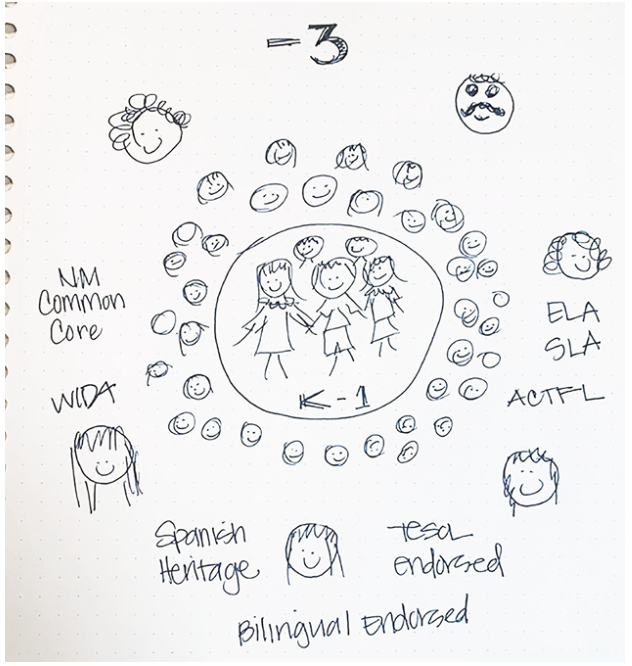

One way to begin using language data better is to make it more visible. You can’t address something that is invisible or not easy to see. In a recent data workshop, I posed questions and asked participants to make a pictorial representation of their answer. Can you tell what was

asked from this sketch?

The data sketches generated a rich conversation around what we know and what we’d like to know. Most important was naming the need for professional learning that centers around how to use data more efficiently and not just pedagogical practices. Those practices, of course, are important too but students cannot turn and talk their way to proficiency. How can we cultivate more robust professional learning experiences that are centered around diverse sets of data? How can we make data CUTE?

Links

1/ https://www.newamerica.org/our-people/leslie-villegas/

3/ https://www.languagemagazine.com/april-2023-inside-the-issue/

4/ https://sdp.cepr.harvard.edu/annual-convening

5/ https://my.visme.co/view/8r41md6e-stakeholder-knowledge-what-are-we-missing

Ayanna Cooper, EdD, is the Pass the Mic series editor, and owner of A. Cooper Consulting. She is the author of And Justice for ELs: A Leader’s Guide to Creating and

Sustaining Equitable Schools (Corwin) and (co-editor) of Black Immigrants in the United States (Peter Lang).